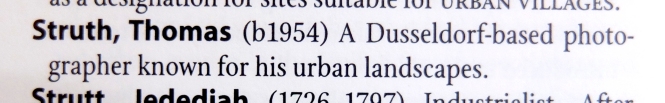

Leafing through the rich and excellent Dictionary of Urbanism by Robert Cowan, I came across an entry for the photographer Thomas Struth:

This led me to search for other urban landscape photographers in the dictionary, but I was disappointed to find no others. Not even Bernd and Hilla Becher, who inspired the ‘Dusseldorf School’ where Thomas Struth and others developed new objective approaches to urban landscape.

So to fill this gap, I propose my own Dictionary of urban photographers.

I have chosen photographers who have influenced popular and professional perceptions of the urban environment. These are photographers looking at land use and built environment, for differing art or documentary purposes. These photographers all contribute to a critical discourse on the image and meaning of the city. They have revealed visual aspects of the city that have changed our understanding of economics, planning and development, social change and equality. These photographers demonstrate the cultural impact of photography in response to the city, as a combination of document, personal interpretation and aesthetic creation. Perhaps they can be included in the edition of the Dictionary of Urbanism….

I am afraid I have not included Thomas Struth.

Berenice Abbott (1898 – 1991)

Photographer, influenced by the writings of Lewis Mumford, who produced Changing New York for the Federal Art Project in the 1930s, documenting the urban environment of New York City and the construction of Manhattan skyscrapers.

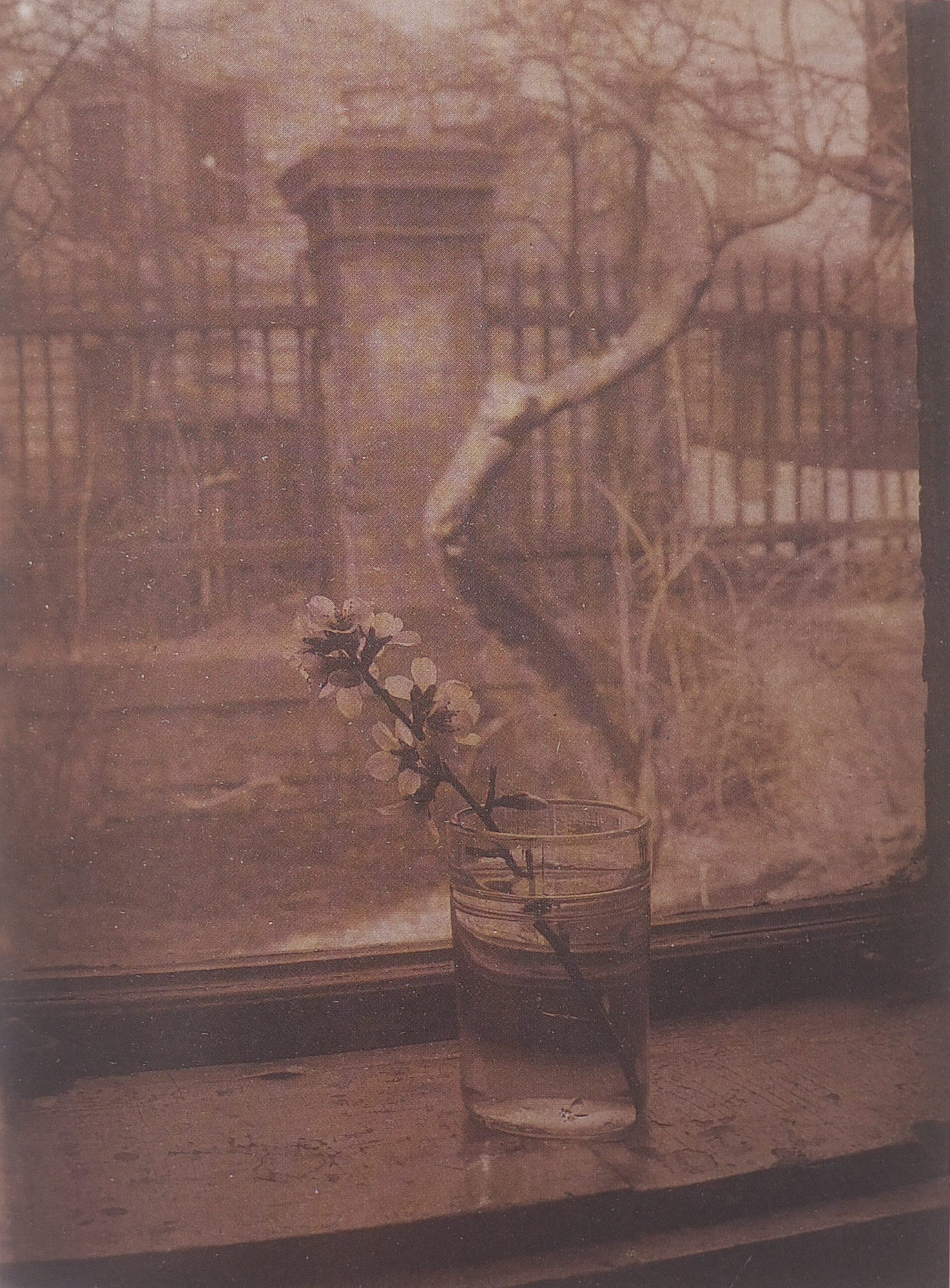

Eugene Atget (1857 – 1927)

French jobbing photographer who documented streets and courtyards of pre-haussmann Paris, whose photographs contributed years later to the picturesque understanding of places, prosaic expediency, the patina of wear and tear, public and private space and the romanticising of urban squalor.

Lewis Baltz (1945 – 2016)

Photographer whose intent scrutiny of American urbanized landscape, provides a commentary on ‘clean’ industrial processes including studies of business parks, production plants, ‘tract’ housing, derelict land, and buildings under construction.

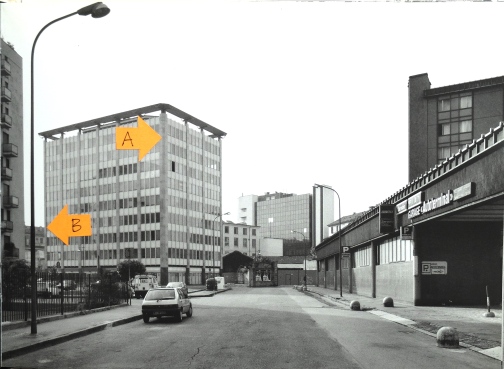

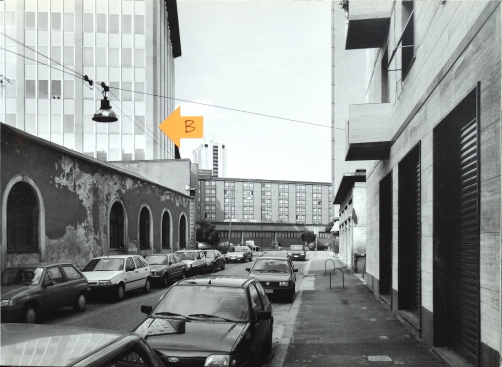

Gabielle Basilico (1944 – 2013)

Italian photographer of cities, trained as an architect in Milan, ‘arguably the best internationally known photographer of urban landscapes’ (The Guardian). As well as many studies of cities, he produced a personal response to Milan’s central business and industrial districts, creating a visual geography. He described himself as ‘a measurer of space’.

Bernd and Hilla Becher (1931 – 2007 and 1934 – 2015)

Artists, famously producing systematic, objective photographic studies of typical industrial and agricultural plant, revealing local variations in the engineering structures of mining, water, gas, steel production, grain storage (which we now call infrastructure): the foundations of the modern city. Founded the ‘Dusseldorf School’ where Andreas Gurskey and Thomas Struth were taught.

John Davies (b1949)

British landscape photographer, who photographs British towns revealing structures of growth and change, the influence of and relationship with the natural landscape and changing industry. Highly legible urban places, often using elevated viewpoints. A seminal 1980s book is Green and Pleasant Land and in 2016 he published a book of coal waste heaps in former mining towns.

Walker Evans (1903 – 1975)

Pioneering photographer who documented the embryonic growth of American settlements in the 1930s associated with industry, showing the early urbanizing effects of the car, new housing and the evolution of ‘main street’ around commercial services.

John Gossage (b1946)

American photographer of the urban environment revealing subtleties of power and influence, in particular The Pond, exploring suburban despoilation of the natural environment, a study of his own privileged neighbourhood, and a study of the places around the Berlin wall.

Andreas Gursky (b1955)

German photographer producing vast-scale photographs of vast-scale industrialised landscape, economic processes and congregations of people, on a scale normally invisible to us.

Lewis Hine (1874 – 1940)

American social documentary photographer who used photography to press for social reform. He was commissioned in 1930 to photograph the construction of the Empire State Building.

Chris Killip (b1946)

Manx photographer, who produced In Flagrante – A devastating visual critique of urban North East England, recognised as among the most important visual records of living in 1980s Britain’ (Wikipedia).

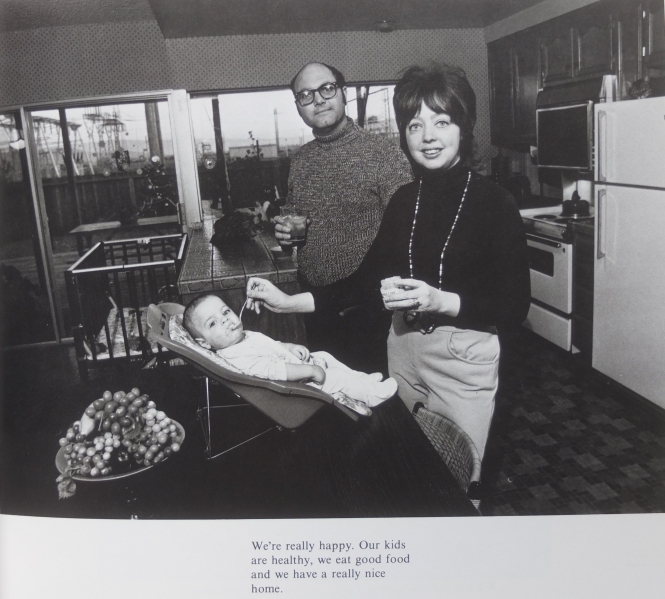

Liisa Sirkka Konttinen (b1948)

Finnish photographer, based in north East England, whose pioneering 1970s Byker showed an urban community on the cusp of dislocation and rehousing. The sympathy in the pictures comes from living as part of the community, influencing social critical photographers since.

Helen Levitt (1913 – 2009)

American photographer and pioneer of street photography, who chronicled the streets of 1940s New York, specifically children’s play.

Stephen Shore (b1947)

Photographer who participated in the influential New Topographics exhibition in 1986, who revealed beauty in the ordinary streetscenes of North American cities randomly chosen, in an impassive ‘deadpan’ aesthetic.