Grasping how difficult it is to define urban design, Francis Tibbalds collected a multitude of ways of expressing the physical, spatial nature of the built environment, the multi-disciplinary and political process of urban change and management. These definitions Included ‘Urban design is everything that you can see out of the window’. A lovely simple idea that puts space between buildings first, architecture second. While it allows urban design to be ‘everything’, it also says that any view is only a small part of the whole urban place.

This prompts an approach to photographing places, whereby the window is a picture frame, like every photograph. It is a ‘given’ outlook, with a meaningful context provided by knowing what interior we are looking out of. The window always gives a partial view, parts of other buildings, parts of roads, a sense of more beyond. This is exactly like photographs, but photographs often take on a false authority that says ‘this is a statement of fixed reality, representing the whole’.

The window is human scale, giving a human view and, we know, just one of hundreds of windows in that place. Windows always face space, they are a defining characteristic of space, the eyes on the street. In a way, Tibbalds gave photography a fantastic role for expressing the idea of places for people – another way of defining urban design.

Most of my photographs here are from the inside of public buildings. There are also four photographs from well-known photographers.

Tony Wilson Place, Manchester, from Home arts centre

Royal Crescent and St Augustine’s Road, Ramsgate from The Churchill Tavern

Museum Street and British Museum, Bloomsbury from a Routemaster bus on New Oxford Street

Sheaf Square and Hallam University, Sheffield from the railway station.

Belsham Street, Hackney, London E9, from my car.

Pancras Square, Kings Cross Quarter from Leon cafe

Leadenhall Market, City of London, from the Lamb Tavern

Gillett Square, Dalston, from the Vortex Jazz Club

Battle Bridge Place, From London St Pancras station

Hoe Street and High Street, Walthamstow from Central Parade, Bread Today and Meanwhile Space workspaces

Boris Savelev, from Secret City, Photographs from the USSR, 1988

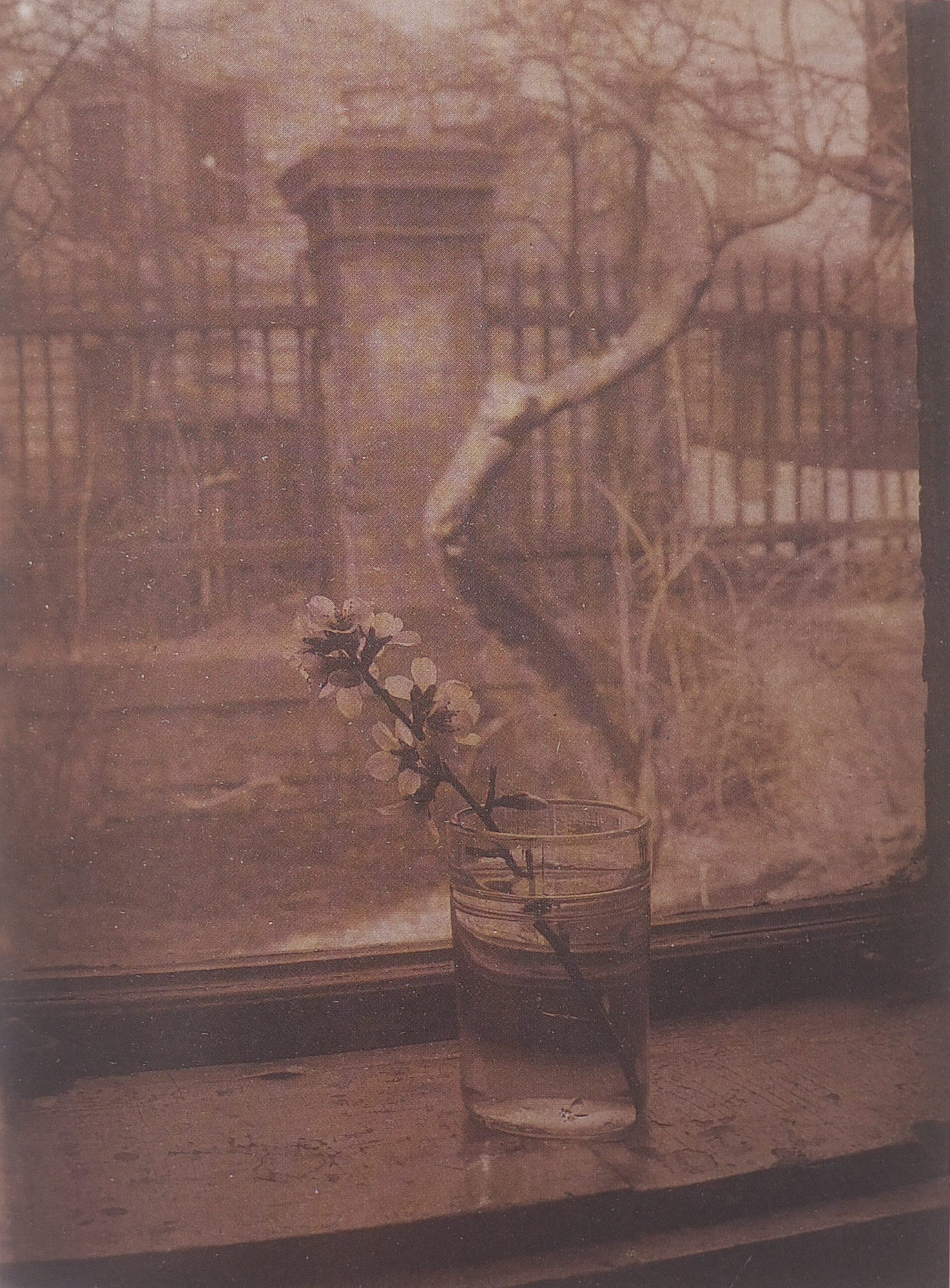

Window of my studio, Josef Sudek, 1950 Studio

Richard Einzig, Pompidou Centre, 1978

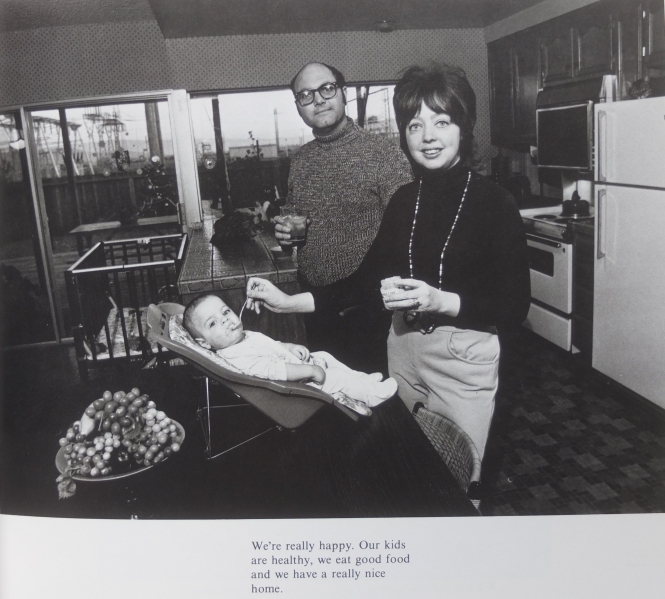

Bill Owens, Suburbia. In this photograph, the view out of the window into the garden shows an extraordinary industrial landscape of gantries beyond, perhaps a railway and power pylons.