In the public perception of planning, photographs make lasting impressions. The public perception of housing is partly based on photographs. Not many of us live there, but we all know Park Hill, the Byker Wall, Harlow and Poundbury through photographs. Photographs are taken for the purposes of description and critique; powerful visual messages are created that praise or disparage.

The products of planning policies and masterplans are large, real places, not easy to understand, even when walking around. A photograph shows fragments of this bigger picture, with documentary clarity about buildings and spaces, their construction, the wear and tear of use. A photograph is evidence of who the housing is for, what it is made from, the urban design solution that was right for that time and place. But the impressions made by selective photographs can also obscure the bigger picture of location, social needs and design ethos; documentary photography is actually often critical photography and sets an image of positivity or negativity.

It was very easy to be damning of modernist architecture through modernist photography – telephoto compressing, stark contrast and lone figures walking with heads bowed. But also true of today’s digitally-managed photography – miniturising, toy-town colour, placing the right people for the intended impression.

Even when writers praise the community, the photos are often about the physicality of the place. Photographs of old housing and community resilience start with Helen Levitt, Roger Mayne, ShirleyBaker, Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen. There was a movement in photography before ‘slum clearance’ that shone a light on bad housing conditions and nostalgicaly celebrated the culture of community and safe play.

Created for a 1943 exhibition called ‘Health’ to get soldiers thinking about Britain’s post-war future. Shown at the ‘Living with Buildings’ exhibition at the Wellcome Collection, Oct 2018 to March 2019. This exhibition examined some of the ways in which architects, planners and designers influence our health, self-esteem and ideas about society. ‘…..the urgent connections between our homes and our health and look anew at the future of our built environment in this major exhibition’.

This page looks at photographs of new housing. Factual, sympathetic and damning photographs of housing estates. The housing estate is where new homes are built to expand the town, to create neighbourhood, to relocate or downsize to. Images of housing estates come to represent feelings about home, images become icons for political views, they are used to characterise planning and to demonise development.

Housing estates house the poorest and the richest. The language has changed: a housing estate is what is built; it becomes home, a place where people grow and have relationships. So ‘estate’ is translated to place, a garden suburb, or a sustainable neighbourhood. Housing estate usually means something planned, new, imposed, as opposed to a place that has evolved over time. Most of our towns are housing estates, the earliest streets were planned and pushed the town outwards, housing for workers. But these streets are not called housing estates. An ‘estate’ is betrayed by culs de sac; when streets link up the estate disappears. Estates are industrially produced places. We mean modern, and housing estates are an aspect of modernism: mass produced, multiple standard units, concrete, brick and tarmac. Some estates grow a community and mature over time, some adapt well to access, social, safety or economic problems, some are radically altered. Photographers photograph them to emphasise an idea or a query – about comfortable living, boring routine, perhaps ennui, of desolation or foreboding; they are often photographed as caricatures of class, of consumption. They photograph the physicality more than the people, often they appear empty, often the people visible are children.

Walker Evans, Birmingham steel mill and workers houses 1936.

In American Photographs, Walker Evans, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

From the essay by Lincoln Kerstein, describing Walker Evans’s photography as ‘… the unrelieved, barefaced, revelatory fact.’ ……’The most characteristic single feature of Evans’s work is its purity, or even its puritanism. It is straight photography, not only in technique but in the rigorous directness of its way of looking.’…..The power of Evans’s work lies in the fact that he so details the effect of circumstances on familiar specimens that the single face, the single house, the single street, strikes with the strength of overwhelming numbers, the terrible cumulative force of thousands of faces, houses and streets.’

Walker Evans, Millworkers houses in Willimantic, Connecticut, 1931

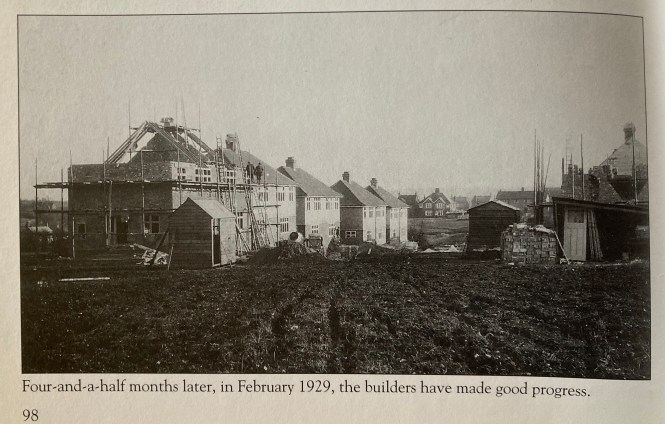

Old photographs of new housing are surprising when they reveal fresh materials and clean lines, before the sagging and patina we associate with each era. All convey optimism and new starts.

Housing under construction outside London in 1929.

New houses, gardens and the sweep of the draughtsman’s road and cut de sac. All fitted on the available land, next to an old footpath, allotments, cemetery, small-holdings and an old terrace of workers’ cottages.

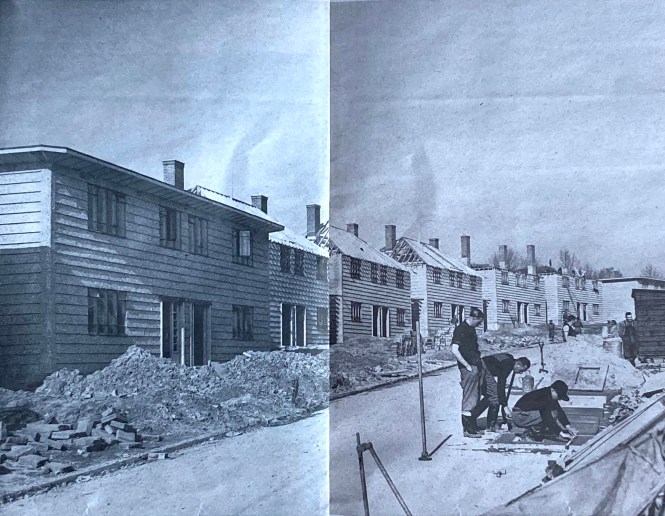

A moment in the modernist revolution when suburban housing conveyed the lines and the hopes of clean, white rationality and enlightenment. An antidote to the high-rise giantism that multiplied but brought disrepute to these ideals. Suburban housing reverted to the romantic ideas of country living.

Prefabricated Airey homes constructed across the country after the second world war, 1947 Corbis / Getty Images. In the immediate post-war period the need for new housing led to experiments with prefabrication, in which concrete panels were manufactured and taken to sites. William Airey and Son produced panels for thousands of new homes.

Stephen Shore, from Uncommon Places

In which Shore exaggerates an alienation, the ennui of lawns, the inescapable road.

Stephen Shore, from Uncommon Places

Tony Ray Jones, photographs from Man Plan 8: Housing, 1970.

Man Plan was a short-lived publication from the Architectural Review that situated architecture in the context of society. Issue 8 was dedicated to housing ….. and considered the impact of new housing on community and wellbeing. Photographs were by Tony Ray-Jones. Shown at The Wellcome Trust exhibition Living With Buildings.

NETHERTHORPE HOUSING ESTATE, TOWARDS WALKLEY, SHEFFIELD, YORKSHIRE, 1981

This housing estate was built in the early 1960’s. The area in front of the tower blocks was purchased by the City in 1887 to become part of the Crookesmoor recreation grounds – which includes the area nearby the Mappin Art Gallery.

John Davies, A Green and Pleasant Land (caption exactly as presented in the book)

Ian Waites, from Middlefield: A post-war council estate in time

‘Greens: At Middlefield, cars were kept ’round the back’, along short, cul-de-sac, service lanes. On the other side – ‘the front’ – short rows of houses were grouped around open green spaces that were either given modern, functional names (The Green) or which were named after nearby deserted mediaeval villages (Dunstall Walk). All was further communal good: “Only then can motorists and pedestrians, who are also sometimes the same people, enjoy the best of both worlds.’

Ian Waites, from Middlefield: A post-war council estate in time

‘….it is May 1964, and my parents and I are viewing what is to be our new home on the estate. Somewhere in the distance a cement mixer churns, creating a metallic loop of sound. My mother pushes the back door open and an audible release of air reverberates through the empty shell of the house, as if it has been hermetically sealed ready for its new tenants. I smell fresh putty and newly plained wood. I see the red and blue dots on the kitchen taps.

‘The Middlefield Lane estate is representative of the post-World War 2 ‘Welfare state’ reconstruction of British society and culture. Between 1945 and 1969, local authorities built around four million dwellings – some 59% of all housing built over that period.

‘Gainsborough was a small provincial Lincolnshire market town at the start of the 1960s with a population of around 17,000 people, but the council was modern, go ahead, and it was busy carrying out a programme of modernisation across the town. Everything was ‘New’.

‘The ‘look’ of this ‘new’ world was defined by the clean, architectural lines of post war modernism, and by experimental ideas and planning which aimed to separate the car from the family. … the pedestrianised nature of the estate in particular gave its children an enormous amount of space to play in….. Its very newness provided them with a blank canvas where a completely new way of life could be created.

Extracts from text by Ian Waites.

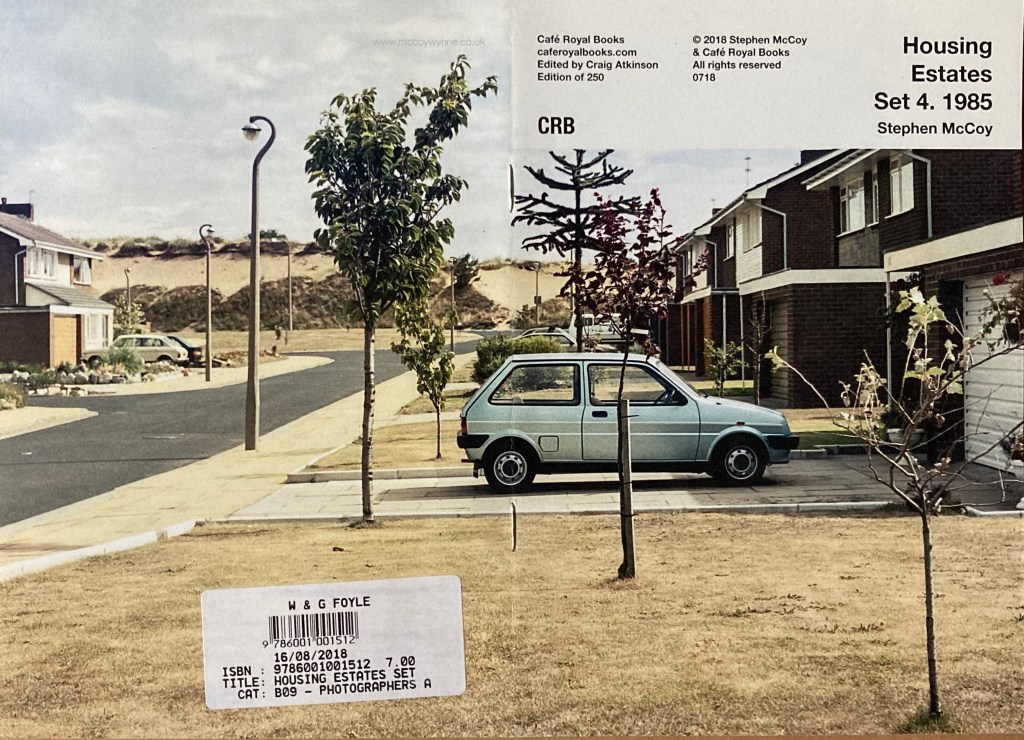

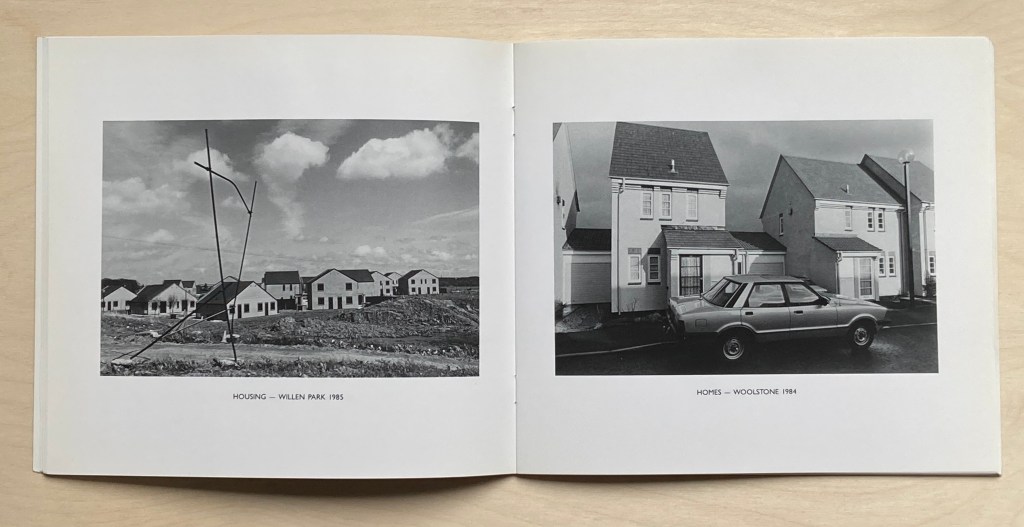

Stephen McCoy, Housing Estates Set 4, 1985 by Stephen McCoy Cafe Royal Books 2018

In this set of photographs Stephen McCoy takes impassive, head-on photographs of houses and garden edges to objectify the architecture of a suburban, owner-occupied housing estate, and lifestyle of the residents.

Bob Jardine, The Promised Land: A Photo Story 1990.

Photographs taken in Milton Keynes, taken as an insider living there. This is about the new town experience ‘concerned with rootlessness and alienation in the face of unrelenting newness…. The presence of the incongruous and the absurd in a totally planned environment.’

Photographs by Ed Thompson, in ‘Welcome to Toy Town’ – article by John Harris, The Guardian Weekend, 6 April 2013.

‘In Camborne near Cambridge, mock-Georgian houses sit next to a replica stone circle, along streets with names such as Quidditch Lane. Can these new developments really recreate traditional village life, John Harris asks, and what is it like to live in them?’

In many respects, Camborne feels like an accurate macrocosm of modern Britain. The pristine, faux traditional houses are the same as those you see all over the country, offering the promise of traditional living with modern comforts. The shops and businesses along the central parade blah blah blah the social fabric of Camborne seems very dependent on private companies most amenities and public spaces come came via section 106 agreements, an innovation from the 1990 planning act, whereby developers can sweeten their pitch to a local council by promising to fund and often build schools, doctors surgeries, community centres and more.

‘Camborne is the gleamingly new build from 1998 onwards and still expanding. Initially it was meant to embody a vision of an eco friendly future in which people would live and work locally. What’s interesting is that its newness seems to have led to a kind of frontier spirit, reflected in amassed drive to make things happen and a palpable local friendliness.’

Nonsuch, Steffi Klenz, 2006. Shown at The Wellcome Trust exhibition Living With Buildings.

‘….In the early 1990s, construction began on an experimental new town, Poundbury in Dorset….The houses’ design is of a traditional style …..It was intended that Poundbury’s design would reduce car use…..’ Extract from caption.

Here the photographer is not only highly selective of surreal compositions but ignorant of the concepts behind Poundbury, which were to achieve a compact village density to optimise use of the land and to create visual narrative; to mix commercial uses and services with housing, make various spaces as locators and group garages behind houses, overlooked by houses for safety. The photographer’s selectivity critiques the traditional aesthetic as alien, and forbidding and misrepresents the housing.

‘In Altonberry, Cambridgeshire, developers are mastering the art of building new homes in large numbers.’ Photograph by Urban and Civic. Article in the Observer Review 21 January 2018 by Rowan Moore, Observer architecture critic.

‘There are more and better ideas being put into practise in British housing than has been the case for decades.’ The article talks of providers of housing other than volume house builders – community groups, local government housing association and small scale builders, the rising popularity of community land trusts, co-housing schemes and cooperatives – with the common belief that a housing project is run by an on behalf of a community. Even property developers show signs of creative thought architecturally intelligent developers producing small projects in the better off parts of the country. Where the whole development is planned as a coherent community. The significance here lies in scale and forethought.

Article in the observer 23rd of September 2018 by Rowan Moore. ‘In Hackney, east London some of the best council-built properties ever built, giving meaning to promises of good design.’ The Kings Crescent estate in Stoke Newington, north London. Photograph by Karakusa vics Carson Architects

Councils fought hard to regain the right to build their own developments to meet local housing need. ‘Council housing’ retained an image of post war estates and then an image of the privatised right to buy your own home. Pioneering Councils arranging the development finance and briefing architects created the outstanding housing of the post-financial crisis period of 2008.

Lilac, sustainable housing in Leeds, offers a small but appealing alternative to conventional developments. Photograph by Simon Dewhurst.

This is a photograph of a block of flats. The message of sustainability is conveyed by a community garden, a mature tree and timber cladding. It is slightly aloof, fresh air but also looking over other (non-sustainable?) rooftops. We don’t know whether it is energy and water efficient, but ‘sustainable’ also says desirable and ethical.