This post is stimulated by the book The View from the Train – Cities and Landscapes by Patrick Keiller.

Woody Allen’s film Manhattan (1979) opens with a sequence of black and white images of the city. It is worth watching the DVD with the sound muted, and pausing on each one. There are 60 consecutive landscape images, each with a fixed movie camera (excluding one from a moving car), some with hustle and bustle movement, fireworks or flashing neon. Here the cinematographer Gordon Willis essentially becomes a still photographer, creating in those 60 images one of the best photographic celebrations of the borough of Manhattan. The images recall photographs by Lewis Hine, William Klein, Helen Levitt, Gary Winogrand and others I’m sure. It is famously overlaid by Gershwin and Woody Allen’s character trying to put his love for the city into words.

I don’t know whether that sequence influenced Patrick Keiller’s films about London: London (1994), Robinson in Space (1997) and Robinson in Ruins (2010), all comprising still images and narration. Keiller lets each image linger for much longer than Allen.

In his book of essays, The View from the Train – Cities and Landscapes (2013), Patrick Keiller talks about how film has influenced our perception and understanding of urban and architectural space. A key point that Keiller makes is that film could not easily be used for critical analysis until technology enabled us to view, stop and start the film.

He describes the origins of his own films, and how his approach is influenced. He discusses a preoccupation with the surrealist movement and how a surrealist sensibility affects all photographic images. Keiller talks about theories of everyday life revealed in photography, and the dilapidating built environment while the financial services economy grows around the ruins.

Patrick Keiller’s films are hardly movies; rather a sequence or collage of static camera images. They look like photographs, but with atmospheric sound and slight movement. A little like the current trend on websites, such as Airbnb, to have a fixed image with a very subtle amount of movement. He also melds the sequence of shots with a fictional, philosophical commentary, giving each film a curious authority about the dismal ennui of places in unnoticed decline. An enduring image is lichen spreading on a trunk road sign.

Paul Kelly’s and Kieran Evans‘s film Finnistere (2003) is influenced by Keiller’s London, with a similar approach of still image combined with narration. But becomes distinctively Kelly’s own interpretation of selected London landscapes with personal commentaries from residents and artists. Paul Kelly’s film What Have You Done Today Mervyn Day (2005) continues with the fixed camera ‘stills’ of deteriorating streets, cafe signs and factory buildings, providing a revealing account of the lower Lea Valley as it awaits the 2012 Olympic Games. In an appreciation of Kelly’s films, the architecture writer Tom Dyckhoff echoes Patrick Keiller’s reference to the philosopher Henri Lefebvre, who described ‘lived space’ as the relationship between a landscape and the people who live within it.

Essays in Keiller’s book consider early 1900s fixed camera, single-take films of places; the fad for the ‘panorama’ shot from the side of a train; and the ‘phantom ride’ filmed by a camera fixed to the front of a train. After publication of this book, Keiller made a film The City of the Future (2023) about the influence of these early films. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/nov/10/2

Since digital ease of selective access to film arrived, there is a wealth of film to be discovered that uses urban landscape as context, character or for narrative meaning in a film. Keiller does not go as far as discussing specific films, but his essays brought to mind a few which resonate with his observations. A notable example is the nine-minute film Rendevous (1976, Claude Lelouch) where the camera is attached to the front of a sports car which travels at high speed, providing a phantom ride through central Paris: along Haussmann’s boulevards and the narrow streets that Eugene Atget photographed.

And in Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) Agnès Varda translates the phantom ride to a taxi windscreen view of Paris, and the panorama to views from a crowded tram, as well as following Cléo walking along the streets, or seeing the street from her own eyes.

Cleo is a depiction of the idling flâneur, an idea originating in situationist actions described by Keiller in his essays. In the first part of Dear Diary (1994, Nani Moretti) (possibly the only film reviewed in the former Blueprint magazine), the forward motion of the phantom ride follows a scooter-rider, who is being another kind of flâneur, idling through and observing Rome’s residential neighbourhoods. Dear Diary owes something to earlier portraits of modern Rome – in Bicycle Thieves and in La Dolce Vita, which is introduced by an aerial panorama of the city following a statue carried by a helicopter.

The character moving through the cityscape in film might reveal a spatial form, or describe a map of the city. Cleo from 5 to 7 does this, as does Bicycle Thieves, and the part of Hannah and her Sisters (1986, Woody Allen) where a character follows someone through the streets of Manhattan’s Soho.

Another manifestation of the phantom ride through urban space is the car chase, most notably in Ronin (1998, John Frankenheimer) where we see a vast extent of Paris in an extended car chase. Or not a car chase (and not a phantom ride), but Minis in The Italian Job (1969, Peter Collinson) driving through the public and private realm of Turin.

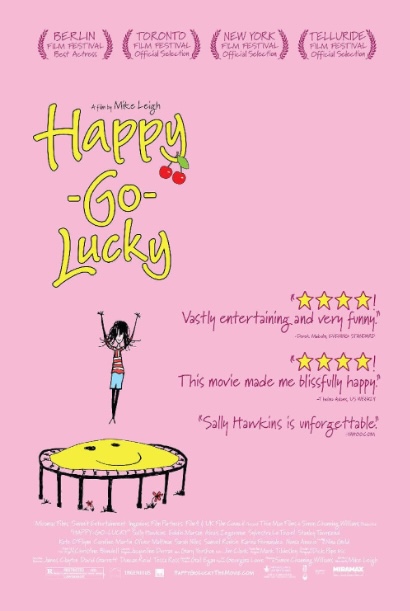

And again from a car, but more mundanely, is the driving lesson in Happy Go Lucky (2014, Mike Leigh). Here we encounter an extended panorama sequence of the ‘lived space’ of residential and slightly dilapidated north London streets, with brick walls, privet hedges, front doors and bins. All incidentally, subliminally, through the side windows of the car.

Film has been used at least twice to deliberately show us architecture – modern housing in Dear Diary and architectural gems in Hannah and her Sisters, where the director shows us his favourite buildings, tenuously linked to the plot. And in Paul Kelly’s Finisterre where we are shown some well-loved modernist housing in London.

Some parts of Keiller’s book are funny, due sometimes to his precise way of elucidating something quite mundane, or his originality in the way he describes early-career explorations of places. And the account of a day visiting London locations with architect Cedric Price is a hoot. But he gives a stimulating and rare consideration of how we see urban landscape as lived space in films.

His book offered me a welcome excuse to talk about some of my tenderly-valued film clips revealing spine-tingling photographic representations of cities.